News

How to Calibrate Your Display

Have you ever bought yarns online and found upon receiving them that the colours were significantly different to the reference picture? Happily, the most common reason for the visual discrepancy is one you have control over: the calibration of your monitor.

While the visual fidelity of computer and television displays has dramatically increased in the past few years, one thing remains unchanged: the default settings for a variety of LCD/LED screens are not optimized for the viewing of images (specifically, the accurate rendering of colour).

In order to fix this shortcoming, you need to calibrate your screen. Right, so you're about to get really techy now, I hear you thinking? No! Luckily, both the Windows and Macintosh (Linux, too, but its users are invariably tech savvy) operating systems contain calibration tools that are easy to use:Windows: Calibrate Display Color

- To access, go to Control Panel > System and Security > Display (or press Windows key + R, then type 'DCCW.exe' into the 'Run' box).

Mac: Display Calibrator Assistant

- To access, go to System Preferences > Displays > Color.

One thing, though: for the best result, ensure that your monitor is set to its native display resolution - often 1360x768 (laptops) or 1920x1080 (desktops) - before running the calibration tool. Also, some recommended that it's better to run the tool around 30 minutes after powering on your screen.

For an overall guide on PC and MAC screen calibration, see this helpful CNET article.

Tablet and smartphone displays cannot be calibrated. However, the IPS panels used by the major brands generally display colour more accurately than their computer counterparts. In some cases, fiddling with the brightness slider can make a difference. For example, with some displays the 100% setting makes yarns appear to be lighter than they actually are. You can get around this problem by setting it to 75% or thereabouts on some devices. One way of verifying that your tablet or smartphone is rendering colours adequately, is to compare and contrast a yarn image with one displayed on, say, a laptop screen you've just calibrated. If they look significantly different, try adjusting the tablet/smartphone's brightness setting until you reach parity with the calibrated display.

That's pretty much it - happy calibrating!

10 Reasons Why Japanese Knitting Books Are The Bee's Knees

Japanese knitting books are my obsession. I didn't realise just how many of these things I had until we moved recently. Boxes and boxes later, I finally came to the conclusion that I have a problem: I think all knitters know 'that' feeling! But I admit it's a good problem to have. These books are SO worth the post-move backache; I look through them regularly and they never get 'old'. So, today, I thought I would share with you 10 reasons why I think these books are the bees knees.

1.

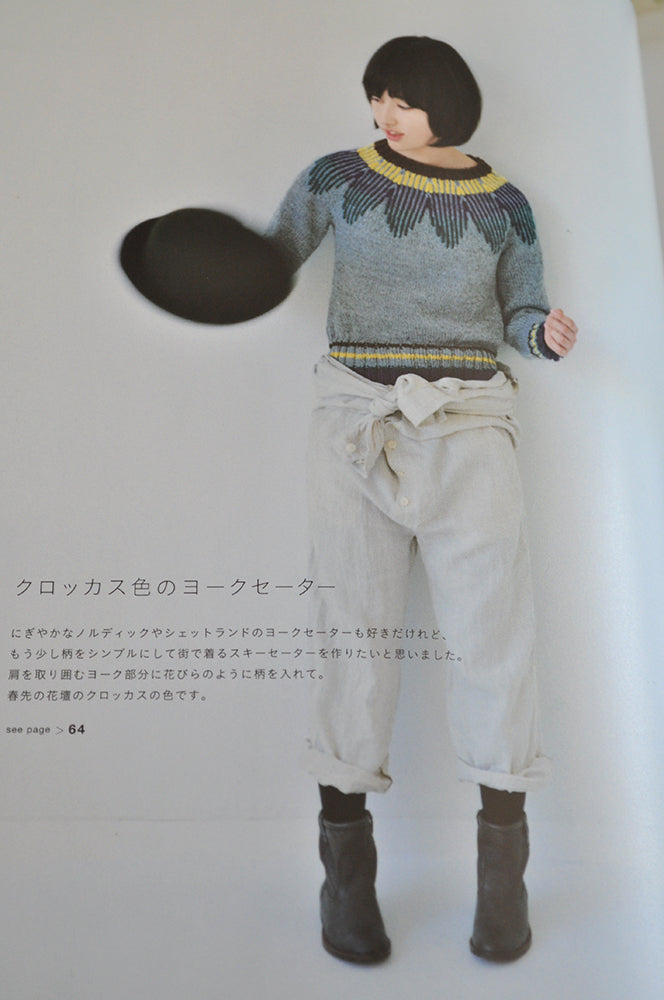

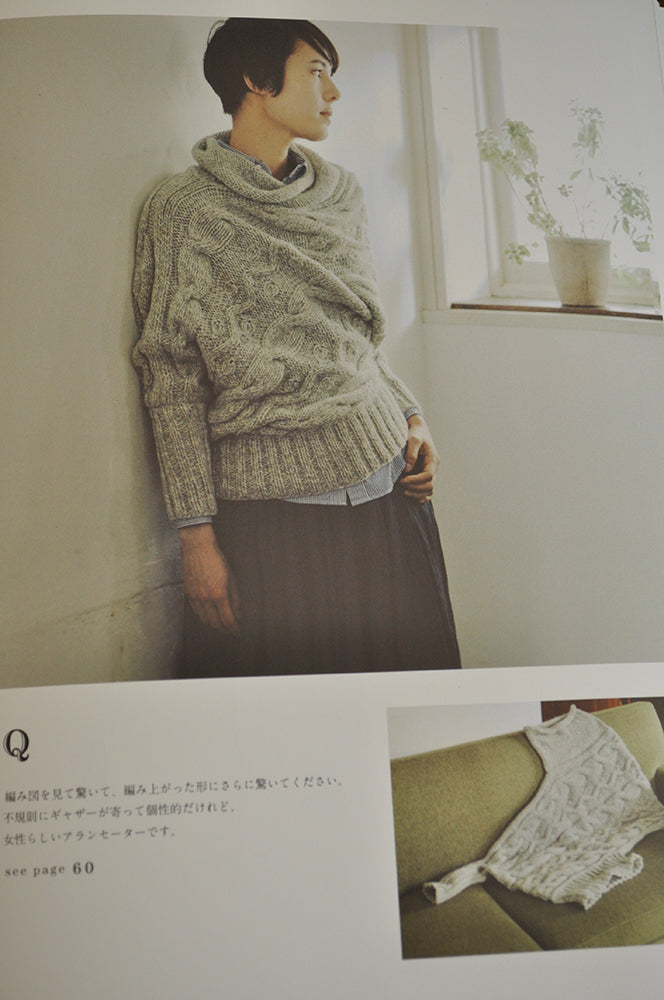

The first thing that always takes my breath away is the photography. Every Japanese knitting book that I have ever seen has beautiful photos, with simple yet stylish backdrops. Their use of light and props gives such a fresh modern look; it's total eye candy and very inspirational.

2.

The second thing is the styling. I love perusing the outfits and the way the knitwear is incorporated into a 'look'. If you're ever after ideas about how to wear your knitwear, check out these books - they are full of inspiration.

3.

The layout of these books is always so pleasing: simple yet organised, making them easy to navigate.

4.

Oh, and let's not forget about the knitwear! Interesting design elements, style, stitch patterns - makes you want to knit EVERYTHING!

5.

Crochet is featured heavily in these books; usually there is an equal number of knitted and crochet items. There are always beautiful garments, shawls and cowls which will make you want to get out the crochet hook and cast on!

6.

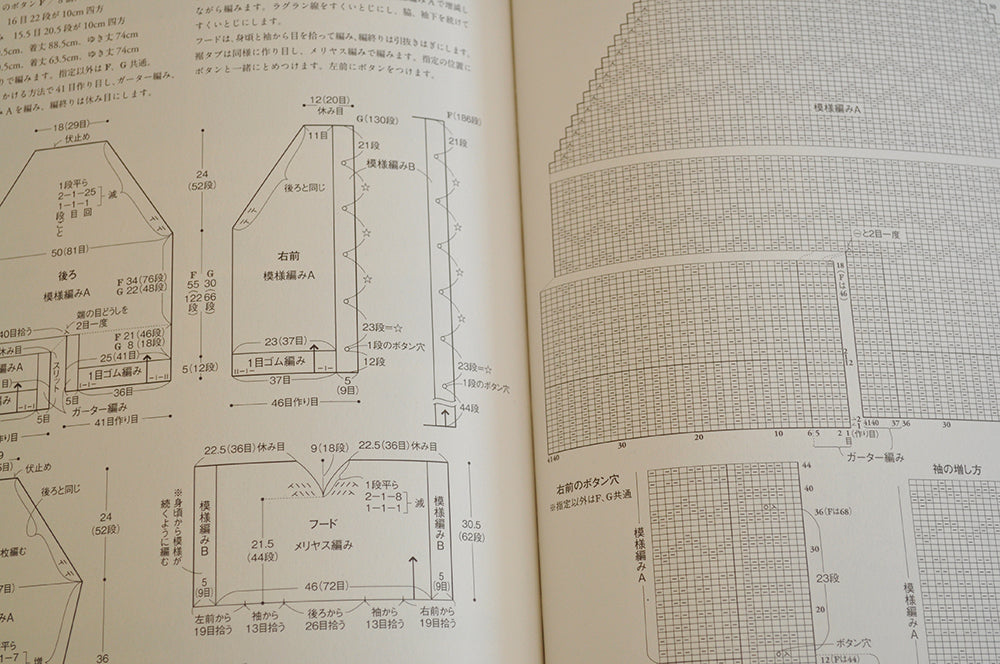

Each book has its own self-contained instruction section, which is usually located at the back of the book. There are LOTS of detailed diagrams showing you how to do all the stitches mentioned in each pattern, as well as special technique diagrams.

8.

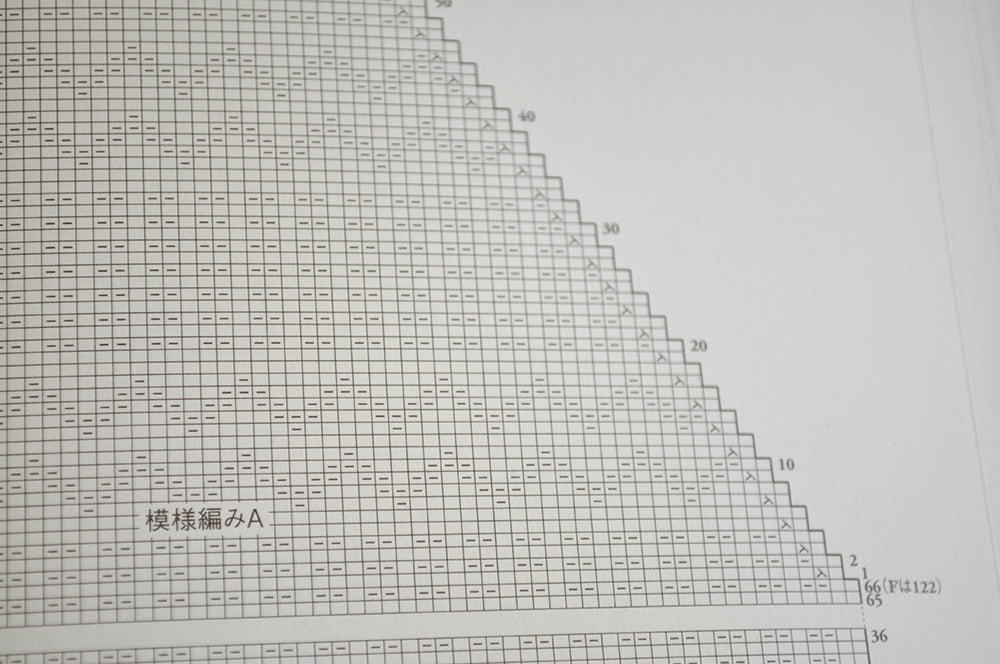

Unlike the western use of written instructions, the Japanese use symbols and graphs for all of their knitting and crochet patterns. This means that their patterns can be read universally with no language barriers.

9.

There are always lots of detailed schematics which provide a wealth of information about size and shape. It's also very handy if you need to make pattern alterations.

10.

There is a HUGE variety of these pattern books available: basic knitting, fair Isle, cables, children, babies, men, blankets, slippers, amigurumi - the list goes on. There's also fabulous stitch dictionaries for both knitting and crochet.

So, if you haven't yet discovered the wonderful world of Japanese knitting books, here's where you can find them!

- Japanese Amazon (you can search in English).

- YesAsia - great shipping rates if you live in Australia.

- Kinokuniya - both online and in store.

- Etsy - I highly recommend Pomadour's Craft Cafe

(I have found that it is easier if you have a book's ISBN number when searching amazon.jp and YesAsia.)

And, if you want more information about how to read Japanese knitting and crochet patterns, check out these links:

- Knitty

- Dancingbarefoot blog

- ABCs of Knitting

- Knitting and Crochet Symbols and Video Guides (scroll to bottom of page for links) from Pierrot Yarns.

Plus if you're keen to tackle a Japanese knitting or crochet patterns, I highly recommend these two books, both of which cover all stitches and symbols that you will find in a Japanese pattern:

- Clear and Simple Knitting Symbols (ISBN 978-4-529-02413-6)

- Clear and Simple Crochet Symbols (ISBN 978-4-529-02412-9)

Happy knitting!

Curious Handmade Summertide Shawl MKAL

We are absolutely delighted to be a part of the Curious Handmade Summertide Mystery KAL! Over the past week we have been having lots of fun putting together colour combinations for this two-coloured shawl, and have finally settled on a group of 12 colourways that will mix'n'match perfectly together.

Now for the fun part, colour combinations! Here are a few ideas and, if you need help deciding on a colour combination, then feel free to contact us.

1. Boho

2. Bold and Bright

3. Chic

4. Chilled Out

5. Minimal

6. Natural

7. Romantic

8. Touch Of Whimsy

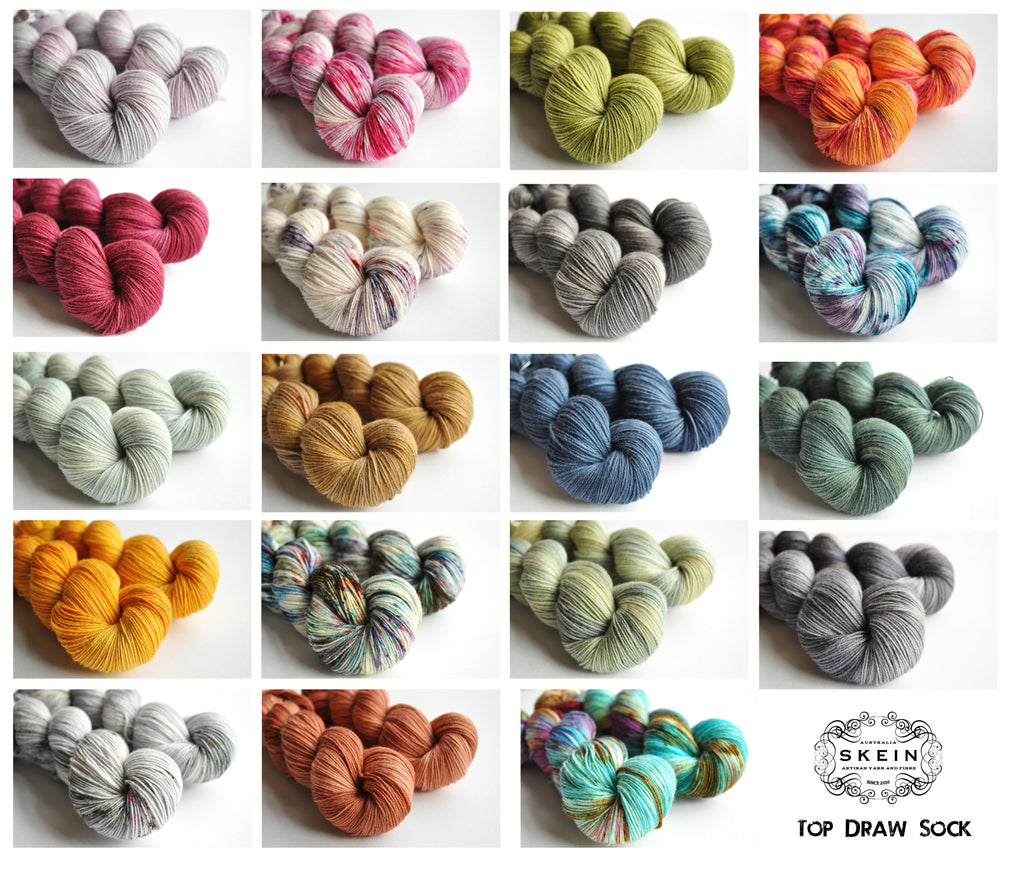

These colourways are now available for pre-order on Top Draw Sock - check them out over on the shop. This shawl calls for two skeins in two different colours, so pick two that you love and you're ready to cast on! Orders will ship the week beginning September 7. The Summertide Shawl MKAL pattern goes on sale September 1, and the first clue will be released September 10. For more information about the Summertide Shawl MKAL, head on over to the Curious Handmade blog.

You may have noticed above new colours, that's because we have just released our new season colourways! You can now see all of our new colourways over on the website.

Have a wonderful weekend!

Your Choice Update

This week, we are testing out a new update format that we think is better tailored to suit you! Here’s how it’s going to work:

- We will be adding three yarn bases to the shop.

- Using a drop-down menu, you will be able to choose the colourway/s YOU want. We have pre-selected 18 colourways that can be dyed onto any of the three yarn bases.

- Your yarns will be dyed up and shipped to you by September 3.

The yarn bases offered for this update will be:

- Uptown Sock

- BFL Sock - 150g skeins

- New!! Voyage DK

Colourways offered for this update will include:

- Caramel

- Early Morning Mist

- Ghost

- Highlands

- Hot Mess

- Ice On The Windowpane

- In The Navy

- Lovey Dove

- Majestic

- Milky Way

- Penny Arcade

- Perfect Day

- Smokestack Lightning

- Thistle

- True Love

- Whisper

- Wintertide

- Wood Smoke

Yarns will be available in store for pre-order from Wednesday 26th August at 12pm AEST until Monday 4th September (unless sold out before).

If you have a certain colourway or yarn that you want to see included in a future update, please head on over to our Ravelry group and tell us in the ’Wish List’ thread. We will try very hard to see that all requests are met.

ALL NEW VOYAGE DK

We are welcoming a brand new yarn to the shop this week called Voyage: a super soft DK yarn that knits up to produce a wonderful, cushy fabric with great stitch definition. Here are the specs:

100% Superwash Merino

230 yards/210 metres in 100g

5-6 sts / inch on 3.75-4.5mm or US 5-7

Gentle machine wash in cold water

Price: $29 AUD

Voyage is available in this week’s pre-order update!

Welcome MCN DK

This week, we are welcoming a new yarn to our shop! MCN DK is a super soft, cushy yarn that knits up to produce a warm, snug fabric with wonderful stitch definition. The addition of cashmere adds a touch of luxury, while the Superwash DK and Nylon makes this yarn ideal for easy to care for items. We are completely in love with the versatility of this yarn, and here are a few patterns that would suit it perfectly:

French Cancan by Mademoiselle C

The Age of Brass and Steam Kerchief by Orange Flower Yarn (free pattern)

A Grey Loop by Helen G (free pattern)

Effortless Cardigan by Hannah Fettig

Surry Hills by Maria Magnusson (Olsson) (free)

Campside Cardi by Alicia Plummer

Asheville Boot Liners by Pam Powers

Hinagiku Hat by 87knit (free)

In this week's update, we have chosen a mix of speckled and semi-solid colourways, which are perfect for showing off texture and lace. Colourways include:- Ice On The Windowpane

- Whisper

- Wood Smoke

- Wintertide

- Majestic

- Ghost

MCN DK is priced at $31 AUD and is currently in store and ready to ship. There are limited amounts available, so be quick!

Happy knitting!

Shearwater

Today we released our newest pattern, Shearwater. Designed to use only one skein of Top Draw Sock, Shearwater features short row-shaping, relaxing garter stitch and a very simple and eye-catching lace border. The result is a light, crescent-shaped shawl that is perfect for summer.

Quick and easy to knit, Shearwater is available now as a free Ravelry download.

Need some Top Draw Sock? Look no further. We have dyed up nineteen colourways that would be perfect for the Shearwater shawl. All yarns are in stock. Simply select your favorite, download the pattern and, voila, your next summer shawl is ready to go!

Friday Highlights

Wow, Friday's sure creep up quickly! I did miss last week, sorry about that! I've had a very busy week and some VERY good news which I will share with you all soon. BUT first thing I would like to do is congratulate Allison who is the winner of the Dale sock kit! She said she would knit the Dale socks using "In the Navy" as the main color and "Penny for your Thoughts" as the contrast. I think that sounds perfect! Please contact me to claim your prize.

So, this week I'm highlighting my favorite Instagram feeds. I am a total Instagram fanatic, there are just so many talented people out there, I am inspired everyday.

From top left - thekitchenwitch, thecraftsessions, bmandarines, chiefandkewpie, warpedthreads, blockshoptextiles, iamalchemy, woollenflower, clo._

Other feeds that I absolutely love but couldn't link to are - designsponge, moonstitches, foxslane and truelymyrtle.

What are your favorite feeds, I would love to know?

Have a wonderful long weekend!

xx

Friday Highlights

Over the past five years, I have had the pleasure of working with designers from around the world who have incorporated Skein into their designs. With shawl season fast approaching, I thought it would be the perfect time to highlight a few of these designs.

Barndom by Stephen West which featured Top Draw Sock in the Hazel colourway. This wonderful design has all the features of an enjoyable and easy project - garter stitch, slipped stitches and stripes! The great part about striped shawls is selecting the colours, make it bright and full of contrast or soft and neutral. Whatever the case this shawl is a lot of fun to knit and wear.

Zébulon by Ariane Caron-Lacoste, this pattern was first released in 2011 and featured Vintage Lace in the colourway Quill. Although Vintage Lace is no longer available it can be substituted with our Silk Merino Lace. The design features easy lace stitches, which would be great for those who have yet to try lace knitting, and it only requires one skein! I love the light, open feel of this shawl, it really is a perfect spring time accessory.

Miss Woodhouse by Paulina Popiolek which featured Merino Silk Sport in the colourway Silver Rose (very similar to Mademoiselle). This stunning lace shawl is for those who want a bit of a challenge, designed for intermediate to advanced knitters this shawl features short rows, patterning on both sides and cables. It truly is beautiful and would make a wonderful wedding shawl or accessory for a special occasion.

Forellen by Playsweetmusic Design which featured Top Draw Sock in the colourway Sea Salt. Knitted sidewise, this shawl features a stockinette body, beautiful cable details and an i-cord edging. Its simple and modern with just the right amount of detail - I think it would look just as wonderful using a bright colour or using a contrast colour for the edging.

Give-away winner!!

Before I go, I am delighted to announce the winner of the Darling Dotty shawl kit! Congratulations to

Friday Highlights

This week we are highlighting yet another new design, this time from the lovely Molly of A Homespun House who designed these super cute socks called Dale. Knit using a traditional Fair Isle design (that was inspired by a similar design used by Molly's grandmother and great grandmother) the Dale socks are knit cuff-down and use Skein Top Draw Sock, in the colourways Barley and Quill.

And if the Dale socks weren't cute enough, Molly has also designed a pair of socks for babies and toddlers called Suesie Dale♥. These are also inspired from a pattern knit by Molly's grandmother and great grandmother and feature a very handy i-cord tie to stop the socks slipping off little feet. Knit from Skein Top Draw Sock, Molly used Geisha and Quill with the contrast colour being Barley. So sweet!

You can check out more of Molly's designs over on Ravelry, she has a wonderful website called A Homespun House that sells project bags, patterns and more, plus she also has a wonderful video podcast that I highly recommend!

Giveaway!

Thanks to Molly we have a Dale sock kit to giveaway which includes the pattern plus one skein of Top Draw Sock and a mini skein in a contrasting colour, your choice of colourways! To enter please leave a comment and tell me what two colourways you would chose to make the Dale socks. One entry per person please, winner will be announced Friday 27th March.

Have a wonderful weekend!

Friday Highlights

This week I'm very happy to be highlighting a brand new shawl design by the talented Libby Jonson called Darling Dotty which uses two skeins of Skein Merino Silk Sport. This lovely feminine shawl features an all over dotty pattern that adds a subtle hint of texture which is finished with a sweet bobble border.

Darling Dotty is crescent shaped, which is so easy to wear and the light, drapey fabric makes a perfect transition piece as we head into autumn here in the southern hemisphere or spring in the north.

Darling Dotty is available as a Ravelry download, all information can be seen here. Libby has a wonderful blog called Truly Myrtle, she has also just started a new podcast under the same name. You can check out more of Libby's designs here.

Giveaway

Thanks to Libby we have a Darling Dotty kit to giveaway which includes the pattern plus two skeins of Skein Merino Silk yarn, your choice of colourway! To enter please leave a comment and tell me what colourway you would chose to make the Darling Dotty shawl. One entry perperson please, winner will be announced Friday 20th March.

Have a wonderful weekend!

Friday Highlights

A new addition to the blog - Friday Highlights is all about showing off customer projects. I am so inspired by people's projects that I though it would be a great idea to share them here every Friday.

Knitter - Christine (aka. yarnaboutyarn)

Pattern - Feather and Fan Cloud by Veera Välimäki

Yarn - Skein DK in the Just So colourway

Check out Christine's project page here.

Knitter - Dianne (aka. Goodgirlsaturday)

Pattern - Climb Every Mountain by Heidi Kirrmaier

Yarn - Skein DK in the Champagne colourways

Check out Dianne's project page here.

Knitter - 9crafty11

Pattern - 3 Color Cashmere Cowl by Joji Locatelli and 3 Colour Cashmere Beanie by 9crafty11

Yarn - Skein Merino Silk Sport in the colourways Wild Apple, Sterling and Sugar

Check out 9crafty11's project page for the cowl here and for the beanie here.

Knitter - Mary (aka mmlt)

Pattern - Just Knit It by Susan Ashcroft

Yarn - Skein Top Draw Sock in the colourway Neon and Grey

Check out Mary's project page for here.

Knitter - Susan (aka supizoo)

Pattern - Crosshaven by Rich Ensor

Yarn - Skein Top Draw Sock in the colourway Raku

Check out Susan's project page for here.

Thank you to Christine, Dianne, 9crafty11, Mary and Susan for allowing me to share your projects.

Have a wonderful weekend!

Madewell

This week we are thrilled to have our yarn featured in Joji Locatelli's newest design Madewell.

Madewell is a simple, easy to wear cardigan with a special design feature - elbow patches! These are of course optional, but really why wouldn't you want them.

Joji used Skein Slinky to create Madewell, this yarn however has sadly been discontinued - BUT you can easily substitute this yarn for our Merino Cashmere Fingering. The colourway Joji used is called Quill.

Details and pattern download can be found over on Ravelry!

All images courtesy of Joji Locatelli